From the Townsend Letter |

||||

Fatigue, Immunity and Inflammation: Their Resolution Using Natural Medicine by Michael Ash, BSc, DO, ND, DipION; Robert Settenari, MS; and Prof. Garth L. Nicolson, PhD |

||||

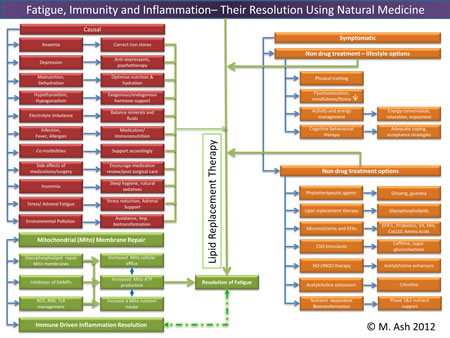

Overview At the biochemical level, fatigue is related to the metabolic energy available to tissues and cells, mainly through mitochondrial electron transport. Electron transport is directly linked to functional, intact inner mitochondrial membranes. Thus the integrity of mitochondrial membranes is critical to cell function and energy metabolism.1 Mechanisms of Fatigue and its Resolution Fatigue: Successful Intervention

Mechanisms of Fatigue and its Resolution

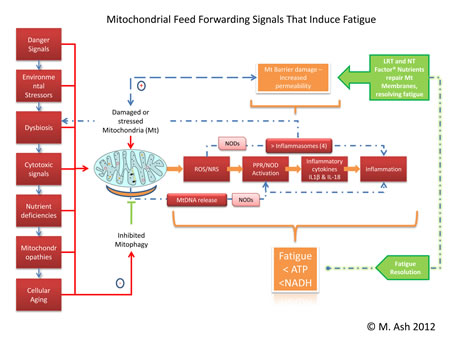

Trouble viewing? Larger image here... (824KB) Mitochondria are responsible for many metabolic circuits and signalling pathways. Just a few examples of these are oxidative phosphorylation, the mechanism our cells use to generate most intracellular ATP (cellular fuel); biosynthesis of key molecules, including heme and certain steroids, as well as in many catabolic–energy relevant pathways such as the β-oxidation of fatty acids; and regulation of calcium homeostasis. Importantly, mitochondria are responsible for production of most of our cell's reactive oxygen species (ROS) and some reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Significant oxidative damage to mitochondrial membranes also represents the point of no return of programmed cell death pathways that culminate in apoptosis or regulated necrosis.19 Immune Inflammation

Healthy mitochondrial function (and death) determines appropriate management of energy production, fatigue control, and innate immune driven inflammation responsiveness. Using LRT administered as a nutritional supplement with antioxidants assures that mitochondrial membrane permeability is maintained in the optimal range, preventing oxidative membrane damage and reducing the number of mitochondrial DNA deletions. Thus LRT can be used to restore mitochondrial and other cellular membrane functions via delivery of undamaged replacement lipids to cellular organelles.34 LRT is not just the dietary substitution of certain lipids with proposed health benefits; it is the actual replacement of damaged cellular lipids with undamaged lipids to ensure proper structure and function of cellular structures, mainly cellular and organelle membranes.12 Inflammation is an essential immune response that enables survival during infection or injury and maintains tissue homeostasis under a variety of noxious conditions. Inflammation comes at the cost of a transient decline in local tissue function, which can in turn contribute to the pathogenesis of diseases and loss of function related to altered homeostasis. Inflammation has been described as the "common soil" of altered health and function.35

Trouble viewing image. Larger version here. (825KB) Resolution of Chronic Conditions

This health-altering intersection of immunity, oxidative stress, and dysbiosis can be found in the membranes of the mitochondria residing in our cells – not only of the gastrointestinal tract but all other tissues as well. The clinical use of LRT has the potential to decrease the effects of aging on mitochondria and improve mitochondrial function in chronic diseases, diminish fatigue, and improve altered states of mucosal immunity through the participatory resolution of inflammasome mediated dysbiosis. The improvement in terms of restitution of mucosal and immunological tolerance has potential health benefits that extend systemically.45

1. Manuel y Keenoy B, Moorkens G, Vertommen J, De Leeuw I. Antioxidant status and lipoprotein peroxidation in chronic fatigue syndrome. Life Sci. 2001 Mar 16;68(17):2037-49. 2. Lewis G, Wessely S: The epidemiology of fatigue: more questions than answers. J Epidemiol Community Health 1992, 46(2):92-97. 3. Cloninger CR. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. A proposal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987 Jun;44(6):573-88. 4. Nelson E, Kirk J, McHugo G, Douglass R, Ohler J, Wasson J, Zubkoff M. Chief complaint fatigue: a longitudinal study from the patient's perspective. Fam Pract Res J. 1987 Summer;6(4):175-88. 5. Nijrolder I, van der Windt DA, van der Horst HE. Prognosis of fatigue and functioning in primary care: a 1-year follow-up study. Ann Fam Med. 2008 Nov-Dec;6(6):519-27. 6. Gunja N, Brown JA. Energy drinks: health risks and toxicity. Med J Aust. 2012 Jan 16;196(1):46-9. 7. Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Kasperski SJ, Vincent KB, Griffiths RR, O'Grady KE. Energy drink consumption and increased risk for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011 Feb;35(2):365-75. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01352.x. Epub 2010 Nov 12. 8. Avellaneda Fernández A, Pérez Martín A, Izquierdo Martínez M, Arruti Bustillo M, Barbado Hernández FJ, de la Cruz Labrado J, Díaz-Delgado Peñas R, Gutiérrez Rivas E, Palacín Delgado C, Rivera Redondo J, Ramón Giménez JR. Chronic fatigue syndrome: aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. BMC Psychiatry. 2009 Oct 23;9 Suppl 1:S1. Review. 9. Nicolson, G.L. and Ellithrope, R. Lipid replacement and antioxidant nutritional therapy for restoring mitochondrial function and reducing fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome and other fatiguing illnesses. J. Chronic Fatigue Syndr. 13(1): 57-68 (2006). View Full Paper 10. Nicolson, G.L. and Settineri, R. Lipid Replacement Therapy: a functional food approach with new formulations for reducing cellular oxidative damage, cancer-associated fatigue and the adverse effects of cancer therapy. Funct. Food Health Dis. 4: 135-160 (2011). View Full Paper 11. Ellithorpe, R.A., Settineri, R., Mitchell, C.A., Jacques, B., Ellithorpe, E. and Nicolson, G.L. Lipid replacement therapy drink containing a glycophospholipid formulation rapidly and significantly reduces fatigue while improving energy and mental clarity. Funct. Food Health Dis. 8: 245-254 (2011). View Full Paper 12. Nicolson GL, Ellithorpe RR, Ayson-Mitchell C, Jacques B, Settineri R. Lipid Replacement Therapy with a Glycophospholipid-Antioxidant-Vitamin Formulation Significantly Reduces Fatigue Within One Week. JANA Vol 13 No1 2010: 10-14 View Full Paper 13. Ströhle A, Wolters M, Hahn A. Micronutrients at the interface between inflammation and infection–ascorbic acid and calciferol: part 1, general overview with a focus on ascorbic acid. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011 Feb;10(1):54-63. Review. 14. Ströhle A, Wolters M, Hahn A.Micronutrients at the interface between inflammation and infection–ascorbic acid and calciferol. Part 2: calciferol and the significance of nutrient supplements. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011 Feb;10(1):64-74. Review. 15. Walsh NP, Gleeson M, Shephard RJ, Gleeson M, Woods JA, Bishop NC, Fleshner M, Green C, Pedersen BK, Hoffman-Goetz L, Rogers CJ, Northoff H, Abbasi A, Simon P. Position statement. Part one: Immune function and exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2011;17:6-63. Review. 16. Walsh NP, Gleeson M, Pyne DB, Nieman DC, Dhabhar FS, Shephard RJ, Oliver SJ, Bermon S, Kajeniene A. Position statement. Part two: Maintaining immune health. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2011;17:64-103. Review. 17. Nicolson GL, Ellithorpe R and Settineri R. Blood homocysteine levels are significantly reduced with a glycophospholipid formulation (NTFactor® plus vitamin B-complex): a retrospective study in older subjects. Paper in Preparation. 18. Piper BF, Dibble SL, Dodd MJ, Weiss MC, Slaughter RE, Paul SM. The revised Piper Fatigue Scale: psychometric evaluation in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998 May;25(4):677-84. 19. Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Brenner C. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in cell death. Physiol Rev. 2007 Jan;87(1):99-163. Review. 20. Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, Englert JA, Rabinovitch M, Cernadas M, Kim HP, Fitzgerald KA, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2011 Mar;12(3):222-30. Epub 2010 Dec 12. 21. Tschopp J. Mitochondria: Sovereign of inflammation? Eur J Immunol. 2011 May;41(5):1196-202. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141436. Review. 22. Franchi L, Muñoz-Planillo R, Núñez G. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat Immunol. 2012 Mar 19;13(4):325-32. doi: 10.1038/ni.2231. 23. Chen GY, Núñez G. Inflammasomes in intestinal inflammation and cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011 Dec;141(6):1986-99. Epub 2011 Oct 15. Review. 24. Stienstra R, van Diepen JA, Tack CJ, Zaki MH, van de Veerdonk FL, Perera D, Neale GA, Hooiveld GJ, Hijmans A, Vroegrijk I, van den Berg S, Romijn J, Rensen PC, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Kanneganti TD.Inflammasome is a central player in the induction of obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Sep 13;108(37):15324-9. Epub 2011 Aug 29. 25. Bansal AS, Bradley AS, Bishop KN, Kiani-Alikhan S, Ford B. Chronic fatigue syndrome, the immune system and viral infection. Brain Behav Immun. 2012 Jan;26(1):24-31. Epub 2011 Jul 2. Review. 26. Maes M, Twisk FN, Kubera M, Ringel K. Evidence for inflammation and activation of cell-mediated immunity in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): increased interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, PMN-elastase, lysozyme and neopterin. J Affect Disord. 2012 Feb;136(3):933-9. Epub 2011 Oct 4. 27. Franklin BS, Latz E. For gut's sake: NLRC4 inflammasomes distinguish friend from foe. Nat Immunol. 2012 Apr 18;13(5):429-31. doi: 10.1038/ni.2289. 28. Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Jin C, Hao L, Mehal WZ, Strowig T, Thaiss CA, Kau AL, Eisenbarth SC, Jurczak MJ, Camporez JP, Shulman GI, Gordon JI, Hoffman HM, Flavell RA. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature. 2012 Feb 1;482(7384):179-85. doi: 10.1038/nature10809. 29. Circu ML, Aw TY. Intestinal redox biology and oxidative stress. Semin Cell Dev Biol. Epub 2012 Mar 30. 30. Maes M. Inflammatory and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways underpinning chronic fatigue, somatization and psychosomatic symptoms. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009 Jan;22(1):75-83. Review. 31. Kelly D, Delday MI, Mulder I. Microbes and microbial effector molecules in treatment of inflammatory disorders. Immunol Rev. 2012 Jan;245(1):27-44. Review. 32. Habil N, Al-Murrani W, Beal J, Foey AD. Probiotic bacterial strains differentially modulate macrophage cytokine production in a strain-dependent and cell subset-specific manner. Benef Microbes. 2011 Dec 1;2(4):283-93. 33. Gómez-Llorente C, Muñoz S, Gil A. Role of Toll-like receptors in the development of immunotolerance mediated by probiotics. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010 Aug;69(3):381-9. Epub 2010 Apr 23. Review. 34. Ellithorpe RR, Settineri R, Nicolson GL. Pilot study: reduction of fatigue by use of a dietary supplement containing glycophospholipids. J Am Nutraceut Assoc. 2003; 6(1): 23-28. 35. Scrivo R, Vasile M, Bartosiewicz I, Valesini G. Inflammation as "common soil" of the multifactorial diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2011 May;10(7):369-74. Epub 2010 Dec 30. Review. 36. Lakhan SE, Kirchgessner A. Gut inflammation in chronic fatigue syndrome. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2010 Oct 12;7:79. 37. Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. The inflammasome: A remote control for metabolic syndrome. Cell Res. Epub 2012 Apr 10. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.55. 38. Hirota SA, Ng J, Lueng A, Khajah M, Parhar K, Li Y, Lam V, Potentier MS, Ng K, Bawa M, McCafferty DM, Rioux KP, Ghosh S, Xavier RJ, Colgan SP, Tschopp J, Muruve D, MacDonald JA, Beck PL. NLRP3 inflammasome plays a key role in the regulation of intestinal homeostasis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Jun;17(6):1359-72. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21478. Epub 2010 Sep 24. 39. Norheim KB, Jonsson G, Omdal R. Biological mechanisms of chronic fatigue. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011 Jun;50(6):1009-18. Epub 2011 Feb 1. Review. 40. Dantzer R, O'Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW: From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008, 9:46-56. 41. Raison CL, Lin JM, Reeves WC: Association of peripheral inflammatory markers with chronic fatigue in a population-based sample. Brain Behav Immun 2009, 23:327-337. 42. Lebeer, S., Vanderleyden, J. & De Keersmaecker, S.C. Host interactions of probiotic bacterial surface molecules: comparison with commensals and pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 171–184 (2010). 43. Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:359-407. Review. 44. Agadjanyan M, Vasilevko V, Ghochikyan A, Berns P, Kesslak P, Settineri R, Nicolson GL. Nutritional supplement (NTFactor) restores mitochondrial function and reduces moderately severe fatigue in aged subjects. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr 2003; 11(3): 23-26. View Full Paper 45. Wu HJ, Wu E. The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes. Epub 2012 Jan 1;3(1). ©2012 Nutri-Link Ltd.

©2012 Nutri-Link Ltd.

|

||||

![]()

Consult your doctor before using any of the treatments found within this site.

![]()

Subscriptions are available for Townsend Letter, the Examiner of Alternative Medicine magazine, which is published 10 times each year.

Search our pre-2001

archives for further information. Older issues of the printed magazine

are also indexed for your convenience.

1983-2001

indices ; recent indices

Once you find the magazines you'd like to order, please use our convenient form, e-mail subscriptions@townsendletter.com, or call 360.385.6021 (PST).

Who are we? | New

articles | Featured topics |

Tables of contents | Subscriptions | Contact

us | Links | Classifieds | Advertise | Alternative

Medicine Conference Calendar | Search site | Archives |

EDTA

Chelation Therapy | Home

© 1983-2012 Townsend Letter for Doctors

& Patients

All rights reserved.

Website by Sandy Hershelman

Designs

![]()

Michael Ash, BSc, DO, ND, F.DipION, founded one of the UK's largest integrated medicine clinics, embedded in the principles and practices of functional medicine. In 2008 he retired from full-time practice after 25 years to concentrate on his many years of clinical and research experience in the manipulation of the mucosal immune system. He presents his and others' work internationally and continues to develop and oversee clinical and research projects for which food concentrates and biological organisms are utilized to aid the restoration and management of mucosal tolerance through the signaling receptors of the innate immune system. Managing director of Nutri-Link Ltd. and Integrative Health Consultants, he maintains a boutique clinical role in which he evolves his research into one-to-one clinical experiences.

Michael Ash, BSc, DO, ND, F.DipION, founded one of the UK's largest integrated medicine clinics, embedded in the principles and practices of functional medicine. In 2008 he retired from full-time practice after 25 years to concentrate on his many years of clinical and research experience in the manipulation of the mucosal immune system. He presents his and others' work internationally and continues to develop and oversee clinical and research projects for which food concentrates and biological organisms are utilized to aid the restoration and management of mucosal tolerance through the signaling receptors of the innate immune system. Managing director of Nutri-Link Ltd. and Integrative Health Consultants, he maintains a boutique clinical role in which he evolves his research into one-to-one clinical experiences.  Robert Settineri, MS, is an independent research consultant responsible for planning, coordinating, and managing clinical research studies. Mr. Settineri coordinated eight clinical original research publications on lipid replacement therapy (LRT). He developed extraction processes and characterizations of phospholipids and is responsible for writing and submitting a patent for NT Factor. Mr. Settineri also published over 35 scientific research articles pertaining to viral immunology. He has received 32 international awards medical film productions. His medical educational films on immunology are used in universities and hospitals throughout the world. In previous pharmaceutical research, he was responsible for preparation of FDA New Drug Applications that helped support drug registration submissions in 80 countries. Mr. Settineri is also senior vice president and a member of the board of directors for the American Nutraceutical Association.

Robert Settineri, MS, is an independent research consultant responsible for planning, coordinating, and managing clinical research studies. Mr. Settineri coordinated eight clinical original research publications on lipid replacement therapy (LRT). He developed extraction processes and characterizations of phospholipids and is responsible for writing and submitting a patent for NT Factor. Mr. Settineri also published over 35 scientific research articles pertaining to viral immunology. He has received 32 international awards medical film productions. His medical educational films on immunology are used in universities and hospitals throughout the world. In previous pharmaceutical research, he was responsible for preparation of FDA New Drug Applications that helped support drug registration submissions in 80 countries. Mr. Settineri is also senior vice president and a member of the board of directors for the American Nutraceutical Association.  Professor Garth L. Nicolson is the president, chief scientific officer, and research professor at the Institute for Molecular Medicine in Huntington Beach, California. He is also a conjoint professor at the University of Newcastle (Australia). He was formally the David Bruton Jr. Chair in Cancer Research and professor and chairman of the Department of Tumor Biology at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and he was professor of internal medicine and professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston. He was also professor of comparative pathology at Texas A & M University. Professor Nicolson has published over 600 medical and scientific papers, including editing 19 books, and he has served on the editorial boards of 30 medical and scientific journals and was a senior editor of four of these. Professor Nicolson has won many awards, such as the Burroughs Wellcome Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine (United Kingdom), Stephen Paget Award of the Metastasis Research Society, the US National Cancer Institute Outstanding Investigator Award, and the Innovative Medicine Award of Canada. He is also a colonel (honorary) of the US Army Special Forces and a US Navy SEAL (honorary) for his work on armed forces and veterans' illnesses.

Professor Garth L. Nicolson is the president, chief scientific officer, and research professor at the Institute for Molecular Medicine in Huntington Beach, California. He is also a conjoint professor at the University of Newcastle (Australia). He was formally the David Bruton Jr. Chair in Cancer Research and professor and chairman of the Department of Tumor Biology at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and he was professor of internal medicine and professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston. He was also professor of comparative pathology at Texas A & M University. Professor Nicolson has published over 600 medical and scientific papers, including editing 19 books, and he has served on the editorial boards of 30 medical and scientific journals and was a senior editor of four of these. Professor Nicolson has won many awards, such as the Burroughs Wellcome Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine (United Kingdom), Stephen Paget Award of the Metastasis Research Society, the US National Cancer Institute Outstanding Investigator Award, and the Innovative Medicine Award of Canada. He is also a colonel (honorary) of the US Army Special Forces and a US Navy SEAL (honorary) for his work on armed forces and veterans' illnesses.