|

Page 1, 2

Abstract

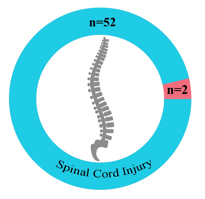

In my role as a practicing physician focused on neurological diseases and insults for over 28 years, I have handled a great many individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Over time, I noticed that an inordinately high percentage of my sporadic ALS patients (sALS) patients presented with specific degenerative bone changes in their vertebral columns. In 2015 I conducted a retrospective study using data from 54 sALS patients whom I handled from 2011 to 2015 who had a CT scan of the cervical and/or lumbar spine. I found that 52 of the 54 had telltale signs of degenerative pathology and a history of spinal injury and (in many instances) reinjury to the original injury site. In order to help insure that my interpretation of the CT scans was accurate, I had a radiologist read them. He found that 52 of the 54 sALS patients had degenerative changes in their spinal columns, consistent with spinal nerve stenosis-induced injuries (but not spinal cord injuries).

These findings, in concert with findings reported by Garbuzova-Davis et al. and Valdes and Garbuzova-Davis, suggest this hypothesis: namely, that an initial traumatic injury to a part of the spinal column (usually the cervical spine) causes degenerative changes of the vertebral bones over time, which acts as a trigger for and player in the development of sALS.1,2 If upheld, the posited linkage will provide researchers and physicians with a risk factor, diagnostic biomarker and etiological player in sALS.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), as originally defined by French neurologist Jean Martin Charcot in 1874, involves the simultaneous involvement of the corticospinal tract and anterior horn cell neurons, the hallmark of which is the selective degeneration of motor neurons in the spinal cord, motor cortex, and brainstem.3,4 At the end of the 19th century, British neurologist William Richard Gowers expanded on Charcot's early research, concluding that multiple progressive diseases affecting both the upper and lower motor neurons, once believed to be distinct, were actually syndromic variations of the same disease.5

The first description of sALS that relates to the hypothesis and findings reported in this article goes back to Gowers, who originally described the onset of the disease as initially affecting a peripheral appendage, then damaging other parts of the same limb as the disease progressed. After manifesting in a single limb, symptoms would then often appear in the other side of the body, particularly in the corresponding limb where the original symptoms began.5,6 While these symptoms still puzzle researchers today, I have witnessed clinically that Gowers's observations hold true for most patients, and are clear hallmarks of the disease. What I found is that the disease often begins initially in areas where spinal injury and reinjury has occurred, which corresponds to motor neurons whose activity has been compromised, which is consistent with the unilateral weakness of the corresponding arm or leg that has been seen to develop soon after such trauma in the vast majority of my patients with sALS (2011–2015).

Hypothesis

A number of risk factors for sALS have been identified; however, no published studies have revealed a specific risk factor that can both trigger disease onset and be treatable so as to remediate, slow, or halt its progression.7 What I have uncovered in sALS patients is a pattern of cervical injury in young adulthood followed in time by arthritic changes and neuroforaminal stenosis. Many years later, a reinjury of the original injury site occurs, and shortly thereafter ALS symptoms develop. These clinical observations led me to posit that an initial cervical injury, followed later by a subsequent reinjury of the same area, is not incidental or inconsequential in sALS sufferers but causes degenerative changes of the vertebral bones over time, which acts as a trigger for and player in the development of sALS.

Materials and Methods

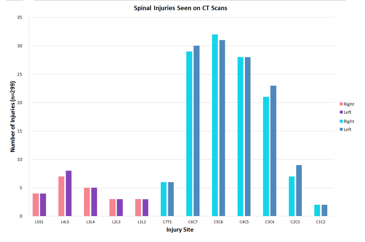

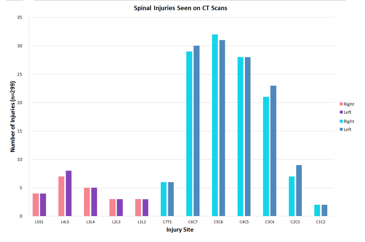

Fifty-four sALS patient charts with CT scans of the neck and spine were selected, dating back to 2011. These represented all of the sALS patients whom I had seen during this 4-year period. Those with and without spinal pathology were included in the analysis. Patients with spinal pathology (n = 52), in the form of identifiable neuroforaminal stenoses visible on their CT scans (n = 336 injuries), then had their injury site coded, tabulated, and graphed by location (cervical, lumbar).

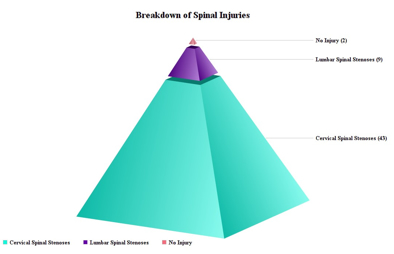

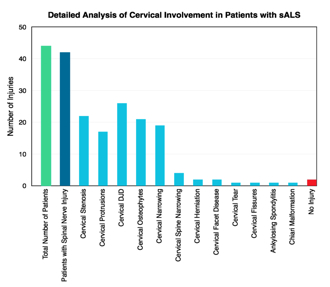

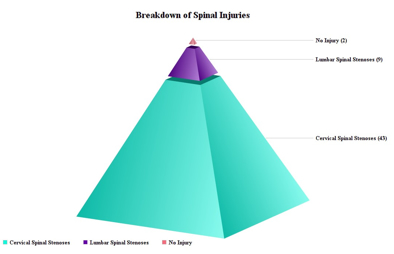

As a primary means of determining the damage in the CNS, I made a point of reviewing the computerized tomography (CT) scans of my sALS patients to identify abnormalities of the cervical spine. I found them to be present in 52 out of my 54 sALS patients. Neuroforaminal stenoses, in particular, indicated areas of potential nerve damage and inflammation, and additional analyses revealed herniation from spinal disc  avulsions, as well as other disc challenges (Figure 1, to the right). avulsions, as well as other disc challenges (Figure 1, to the right).

A radiologist reviewed the CT scans and concurred with what I had seen and noted in terms of cervical bone pathology.

Figure 2, below, reveals that while some injuries were more common than others, the sheer magnitude of the documented injuries indicates a distinctive trend in the sALS population whom I studied.

Though the injuries may have been sustained in different locations along the spine (with most being cervical) and at different times throughout the patients' lives, the commonality is clear. And when compared with healthy individuals, these injuries clearly signal that repetitive spinal trauma is a unique risk factor for the disease (especially when it produces some type of spinal motor neuron constriction and or avulsion upon reinjury). Also, in my experience, if the patient does not have evidence of vertebral column bony pathology consistent with a constriction, avulsion, or injury of at least one spinal motor neuron, and in particular does not have cervical neuroforaminal stenoses, the original diagnosis of sALS should be reevaluated and other conditions considered anew.

What is especially telling about my simple study is this: In at least one anatomical study involving cadavers, it was revealed that 4.9% of adults had evidence of cervical stenoses.8 With there being 12,187 ALS patients in the US, according to CDC statistics published in 2010–2011, 1 in 20 individuals would be expected to have evidence of cervical stenoses.9 In my study population of 54 sALS patient, one would expect to see 2.65 cases of cervical stenosis, whereas I documented 52 cases in total.

Discussion

Trauma as a risk factor and antecedent trigger for sALS has been detailed in epidemiological studies for many years, while conflicting and contradictory evidence have left the research community unsure as to the connection between single incidence trauma, multiple incidences of trauma and the initiation and pathoprogression of sALS.2 For scientists investigating single incidences of trauma, the correlation between such events and the disease are nearly nonexistent in many cases and tenuous at best in others.10 However, for researchers who have studied patients with multiple traumas, the relationships are clear and are seen to have significant correlations to the damage seen in the CNS.11 By investigating populations with a higher incidence of repeated trauma, such as athletes and soldiers, scientists have posited that trauma be considered as a risk factor or trigger for the disease.11,12 However, while some studies have even found that military veterans who experience head injuries, for example, are as much as 2.33 times more likely to develop ALS than other veterans who avoided such traumas, current reports lack detailed documentation of the exact damage sustained.13

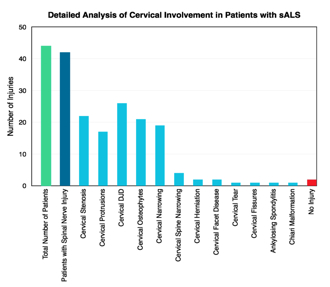

Physicians who do neurologic exams of patients with trauma-related motor neuron issues, or other suspected conditions involving compromised motor neuron functioning or degeneration, routinely have cervical spine CT scans one to rule out cervical myelopathy or radiculopathy as treatable causes following the onset of symptoms. During 40 years of clinical practice, I have noted and casually evaluated the relationship between sALS and cervical vertebral osteoarthritis, disc compression, disc avulsion, neuroforaminal stenosis, and so on of the cervical spine, as seen on CT, MRI, and X-rays in patients of mine suffering from the disease (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3

|

Regrettably, the correlations that I found were dismissed out of hand by specialist colleagues, all of whom indicated that these abnormalities of bony structures of the spine had no bearing on the disease, since no cord compression was seen. On the other hand, my clinical sense told me that there had to be some type of relationship between the consistency of vertebral bony structural abnormalities routinely seen in ALS patients' CT scans and the etiology of the disease. |

| Contrary to common neurological teachings and dogma concerning this disease, my patients presented with outright neck or back pain and/or chronic aches and discomfort involving the posterior neck. These symptoms were usually present for many years, to the point that they are deemed relatively "normal" by them. When vigorously palpated, the areas overlying the neuroforaminal stenoses as seen on the CT are tender and painful, indicating a chronic inflammatory process. Published research into disc herniations and avulsions indicate that there is a strong correlation between spinal nerve compression and greater pain sensitivity, due to the fact that spinal injuries such as these cause decreased blood flow, not only in the spinal nerve but also in the connected nerve fibers that radiate pain to the corresponding extremities.14 |

Figure 4 |

Page 1, 2

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

avulsions, as well as other disc challenges (

avulsions, as well as other disc challenges (